From that moment forward, Siddiqua vowed to advocate for others in a similar situation. She set out to connect with marginalized patient groups and educate her community about disease prevention, nutrition, and healthcare options.

Throughout high school and college, Siddiqua’s free time was spent volunteering across Houston, TX—at Memorial Hermann Hospital where she scribed patient notes for doctors, at the Houston Food Bank where she packed food boxes to be delivered to local charities and shelters, at United Muslim Relief where she made lunches for underserved communities, and at Healthcare for the Homeless where she shadowed a group of physicians who care for the city’s 6,000 plus homeless population.

“I got to see firsthand how local organizations came together to help people in tough situations,” she recalls. “I realized that there were a lot of great resources in Houston and a lot of great people devoted to serving that community. It was humbling but it was also empowering.”

Talking with Siddiqua, it’s easy to see why this first semester student at American University of the Caribbean School of Medicine (AUC) was awarded the school’s Community Outreach Scholarship. The award, which provides a $10,000 toward tuition for up to three semesters, celebrates students who exhibit an exceptional dedication to their communities, hospitals, or charities. Siddiqua happens to be dedicated to all three.

“My goal is to work at a nonprofit hospital or nonprofit organization,” she says. “I haven’t narrowed in on a particular field or specialty but I know that I want to continue to do community work, provide a continuum of care, and see patients who are uninsured. I want to be in a position where I never have to turn a patient away.”

Drawing Parallels Abroad

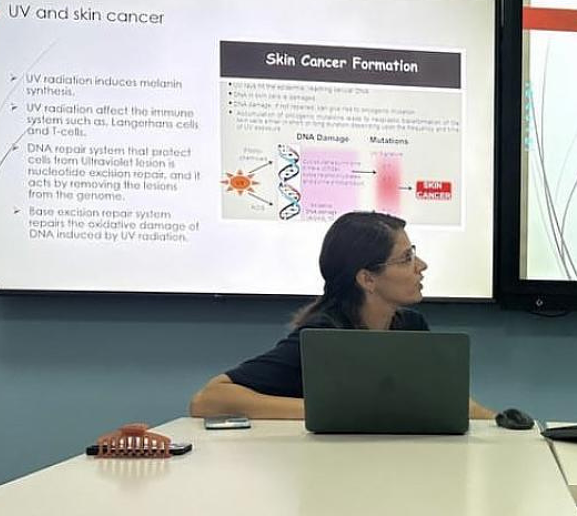

In 2015, the University of Houston selected Siddiqua as a Medicine, Education, and Research through International Travel (MERIT) Scholar. She took a semester-long course to prepare for a medical mission trip to Chennai, India and made the 10-day visit one year ago this month.

She remembers the short but impactful trip vividly.

On one of her first days, Siddiqua met an 8 year-old boy who spoke English and helped as a translator. He was smart and inquisitive but shared that his schooling had recently stopped due to a lack of funding.

“It broke my heart,” she recalls. “Here was a boy with so little, who couldn’t even continue his education, but he was so kind and appreciative. It opened my eyes to how much we take for granted.”

During her 10-day trip, Siddiqua assisted medical providers as they worked with more than 1,400 patients. She taught children about nutrition, educated villages on mosquito prevention techniques, and even helped to clean a gangrenous foot wound of an elderly diabetic man. One of her primary responsibilities was teaching women about basic hygiene and family planning. She and other volunteers used cyclebeads (a string of colored beads) to help women track the days before their next menstrual cycle and understand their fertility risk. They also left behind handmade flipbooks to help women with coping techniques to manage stress.

For many of her patients—predominantly in their 30s and 40s—this was their first time hearing these lessons and their first time seeing a doctor. They will likely have to wait for the next group of missionaries to be seen again.

“Watching how much the doctors could do for these people—and with very limited resources—was inspiring,” she says. “I want to be able to give back in that capacity. The trip definitely reaffirmed my drive toward medicine.”

Despite being thousands of miles from Houston, Siddiqua couldn’t help but to draw parallels between what she saw in India and what she had witnessed in her own community. The environments were different, the diseases and challenges more progressed, but there were still the same problems with access to care.

The Road Ahead

Her formal medical education may be just beginning but Siddiqua already knows the kind of physician she wants to be. Having seen health inequalities at home and around the world, she understands that to effect change, she will need to be an activist and advocate.

She’s reminded in particular of her colleagues at the Healthcare for the Homeless clinic back in Houston. While working with individuals suffering from psychotic episodes, she would often find the physicians—sans white coat—speaking calming, reassuringly, and respectfully to their patients. It’s a picture etched in her memory and one that she aspires to emulate.

“I hope that as a physician I can advocate for my patients in a system where they sometimes lack a voice. Most of all, I hope to one day treat patients like my grandmother and like those in India.”